June 6, 1944

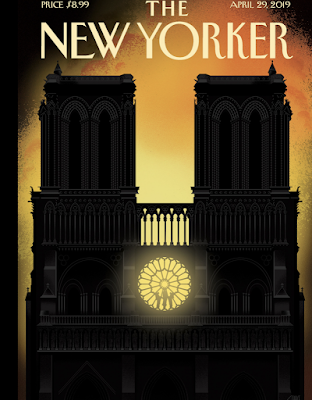

One of the highlights of my week is opening the mailbox and seeing the New Yorker cover. It’s alway a treat. Sometimes it’s just a nice picture but more often the artist pinpoints a moment in our collective consciousness. Like the silhouette of Notre Dame cathedral before a fiery background, titled “Our Lady.”

It makes universal a grief that transcended national and religious differences. Our Lady survived the fire and the people are already at work restoring her. There are flames behind her but the orange and yellow could also be the sunrise and we’re reminded that “The light shines in the darkness and the darkness cannot put it out.”

As Francoise Mouly, the New Yorker’s art director, said in an interview with Lawrence Weschler, “The artist doesn’t function in a vacuum. He doesn’t create the feeling that is in the air, but he has a way of catalyzing it and forcing one’s attention to it.”

I have a book of all the New Yorker covers from the very first, February 1, 1925 up to 1989. It’s a treasure. All those issues, all exactly the same size, week after week. One in particular grabs my attention—July 15, 1944-and today is a good day to talk about it. It commemorated D Day, the invasion by allied forces on the coast of occupied France.

The artist, Rea Irvin, depicted the planning and execution of that monumental effort in the style of the Bayeux Tapestry.

What’s the Bayeux Tapestry? It’s not actually a tapestry but embroidered wool on linen. Measuring 20 inches by 230 inches, it un-scrolls from left to right like a movie reel to tell the story of a momentous event in our history.

1066 is a date everyone knows; the Battle of Hastings and William the Conqueror are familiar to us all from History class. Remember the story? Duke William of Normandy decided to cross the English Channel and invade England. He gathered his forces at Saint Valery-sur-Somme, building long boats, powered by wind and oars, big enough to carry soldiers and horses.

Then he crossed the Channel and landed at Pevensy. He defeated Edward the Confessor, King of England, at the Battle of Hastings,

became William the Conquerer, and ruled England. It’s a turning point in Western Civilization.

In the days before Gutenberg the Bayeux Tapestry told this story and preserved it for history.

Then comes 1944, and the world is overrun by the forces of evil—Nazi Germany occupies most of Western Europe. Now an invasion is planned to cross the channel again, not to conquer France but to liberate her. This was Operation Overlord, the largest seaborne invasion in history, the greatest amphibious operation ever launched. It was a mighty endeavor, a great and noble undertaking.

Rea Irwin told the story with the same colors as we see in the tapestry. Instead of 23 by 230 inches, he had only 7 by 10 inches to tell the story, so he used a comic book format.

In the first row of images we see the Allied leaders planning in secrecy; King George of England, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Then we see Field Marshall Montgomery and Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, (I don’t know why Irwin made the slim Eisenhower so chubby.) Above them are the words, “George Rex, absit invidia: Monty et Ike.” “Absit invidia” means “no offense.” It was meant to deflect the evil eye, “lest the hubris of the braggart attract jealous deities.” There were all sorts of prayers being raised. This was a daring venture with much depending on the weather and no guarantee of success. When it was time, Eisenhower said, "Okay, Let's go."

In the second row, the invasion—landing craft loaded with troops, soldiers coming to shore, one swimming, and in the background a massive fleet of battle ships with planes and parachuters overhead. Above, as in the tapestry, are the words “Mare Navigavit” or "sail the sea" and the date, June 6,1944 AD in Latin numerals. What would William the Conquerer have thought of such a navy? 6,000 ships!

In the third row is the battle; one frame shows tanks and a soldier with a bayonet confronting the Nazi’s in green uniforms. Above this image it says “Bayeux-June VII; allied forces landed there the next day. In the next frame Cowardly Hitler hides under a table in his bunker. Above him it says “sic semper tyrannis.” On the bottom we see rats fleeing.

This was the triumph of democracy over totalitarianism. This week, the seventy-fifth anniversary, everyone will be making speeches and honoring the brave sacrifice of so many. We mustn't forget that they saved the world.

I admire the way this artist memorialized it for us. By replicating the style of the Bayeux tapestry, Rea Irvin placed the Normandy Invasion firmly in the annals of history, in the company of heroic events.

It makes universal a grief that transcended national and religious differences. Our Lady survived the fire and the people are already at work restoring her. There are flames behind her but the orange and yellow could also be the sunrise and we’re reminded that “The light shines in the darkness and the darkness cannot put it out.”

As Francoise Mouly, the New Yorker’s art director, said in an interview with Lawrence Weschler, “The artist doesn’t function in a vacuum. He doesn’t create the feeling that is in the air, but he has a way of catalyzing it and forcing one’s attention to it.”

I have a book of all the New Yorker covers from the very first, February 1, 1925 up to 1989. It’s a treasure. All those issues, all exactly the same size, week after week. One in particular grabs my attention—July 15, 1944-and today is a good day to talk about it. It commemorated D Day, the invasion by allied forces on the coast of occupied France.

The artist, Rea Irvin, depicted the planning and execution of that monumental effort in the style of the Bayeux Tapestry.

What’s the Bayeux Tapestry? It’s not actually a tapestry but embroidered wool on linen. Measuring 20 inches by 230 inches, it un-scrolls from left to right like a movie reel to tell the story of a momentous event in our history.

1066 is a date everyone knows; the Battle of Hastings and William the Conqueror are familiar to us all from History class. Remember the story? Duke William of Normandy decided to cross the English Channel and invade England. He gathered his forces at Saint Valery-sur-Somme, building long boats, powered by wind and oars, big enough to carry soldiers and horses.

Then he crossed the Channel and landed at Pevensy. He defeated Edward the Confessor, King of England, at the Battle of Hastings,

became William the Conquerer, and ruled England. It’s a turning point in Western Civilization.

In the days before Gutenberg the Bayeux Tapestry told this story and preserved it for history.

Then comes 1944, and the world is overrun by the forces of evil—Nazi Germany occupies most of Western Europe. Now an invasion is planned to cross the channel again, not to conquer France but to liberate her. This was Operation Overlord, the largest seaborne invasion in history, the greatest amphibious operation ever launched. It was a mighty endeavor, a great and noble undertaking.

Rea Irwin told the story with the same colors as we see in the tapestry. Instead of 23 by 230 inches, he had only 7 by 10 inches to tell the story, so he used a comic book format.

In the second row, the invasion—landing craft loaded with troops, soldiers coming to shore, one swimming, and in the background a massive fleet of battle ships with planes and parachuters overhead. Above, as in the tapestry, are the words “Mare Navigavit” or "sail the sea" and the date, June 6,1944 AD in Latin numerals. What would William the Conquerer have thought of such a navy? 6,000 ships!

In the third row is the battle; one frame shows tanks and a soldier with a bayonet confronting the Nazi’s in green uniforms. Above this image it says “Bayeux-June VII; allied forces landed there the next day. In the next frame Cowardly Hitler hides under a table in his bunker. Above him it says “sic semper tyrannis.” On the bottom we see rats fleeing.

This was the triumph of democracy over totalitarianism. This week, the seventy-fifth anniversary, everyone will be making speeches and honoring the brave sacrifice of so many. We mustn't forget that they saved the world.

I admire the way this artist memorialized it for us. By replicating the style of the Bayeux tapestry, Rea Irvin placed the Normandy Invasion firmly in the annals of history, in the company of heroic events.

Comments

Post a Comment